Invitation

HOMAGEs

01.06.23, 17:00—19:00

Location

Theodor Barth & Mariann Komissar, Idunsgate 3b, 0178 Oslo, Norway (Doorbell 102, 4th floor)

Info

As he was about to submit the work and reflection for his PhD in artistic research, furniture designer Bjørn Blikstad accepted a commission in the kitchen of his mentor. The brief: make a side-table with overarching shelves and a built-in element from an old hospital apothecary (Ullevål). At HULIAS we decided that we would host a vernissage outside the premises of the gallery, to tease out insights on place-making that are more striking in a home than in a gallery. For the obvious reason that a home is dedicated to place-making, while the gallery is rather dedicated to events.

Though the HULIAS gallery in Maridalsveien 3 focuses on spatially oriented practices—verging unto artistic research—none of the exhibits hosted in the space are functionally dedicated to domestic placemaking. It is a public space weft into the city-plan of Oslo: it is a witness of rock and clay; of solid and slippery foundations. The point of going home with Blikstad is linked to his work-in-progress with his PhD project Level up, exhibited in the HULIAS space May 8th through 30th in 2021. At that time, our house-critic Igory Mansotti pointed the relevance of the provenance.

Not only Blikstad’s forays from the steles of Greek antiquity, through Tilman Riemenschneider’s furry Magdalene of Münnerstadt back to the early Egyptian mythic symbolism of Taweret—the hippo-crocodile-lion mother—but also to the fact that much of the work was done at Blikstad’s home in Trysil (owing to the lockdown during the pandemic). In this exhibit we are moving the question. Instead of asking wherefrom? we are now asking whereto? As of this date, there is no PhD in furniture design. And so we ask: how does artistic research apply? Does it articulate, for instance, in a home?

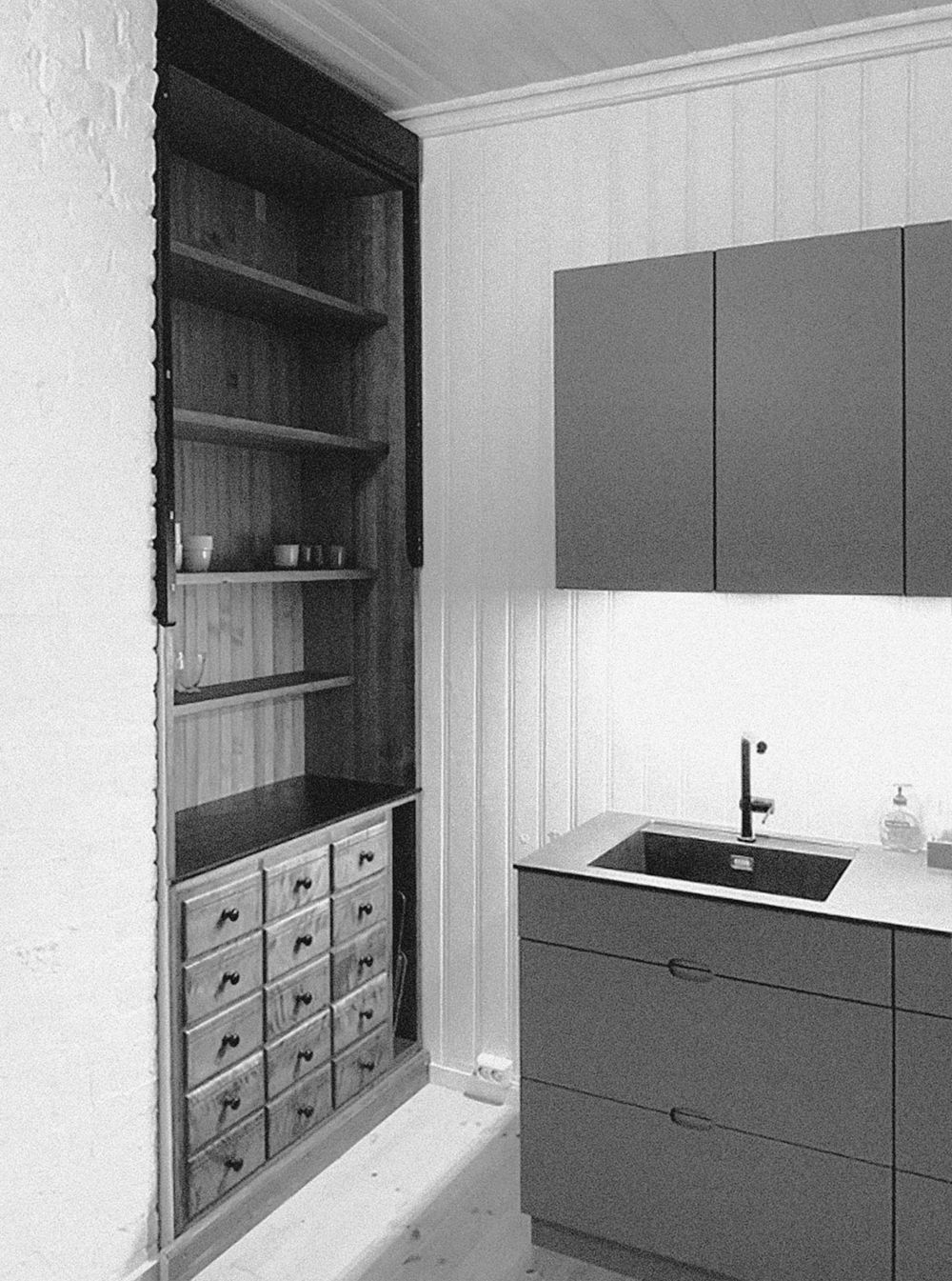

The piece (left) is called homage to Igory Mansotti. It is made from materials left over from Blikstad’s PhD project. This was not done from environmental concerns mainly, but to frame the work within the resource management of a regular workshop where something like this could have come out. The woodwork is mainly in fir. The lighter parts are rubbed with walnut stain. The darker elements are oak tinted with a tincture of steel-wool and vinegar. The carved ornamental work in the piece are restricted to such blacked ebony-like areas: they are almost invisible. They are counter-balanced of the number of asymmetric elements featuring in the homage. It seeks and invents the resident principles.

This is a term coined by British joiner—furniture and interior designer—Norman Potter, whose literalist precepts (1990) always recommends a fresh start, but proceeds in § 2-3 of a list of 20 precepts enjoining the designer to: “2. Seek always the resident principles; 3. Find them where they belong—in the job itself.” Though he thereby formulates the invention of resident principles, as they are intercepted and moved on to the job, of which he shows different examples (notably in two kitchens; one in London, one in a cottage, advocating the kitchen as a place to be). At the vernissage we want to propose a discussion based on this.

We wish to explore the possibility of a functional—rather than added—definition of ornaments. That is, to explore options alternative to ornaments as a decorative add-on, accused by e.g. Adolf Loos (1908), and that the degenerative implications he points out, might be linked to degenerative aspects of design-practices, rather than to ornamentation itself. Instead, we want to discuss the ornamental affordance to hold-in-pattern such aspects of the site, location and place that regularly escape us, because they define one step off of what is functionally linked to our bodies.

That is, the qualities of the site, location and place that are not body-centric, but are still essential to bring out spatial qualities of what we would call a home. Including the myths, fetiches and ghosts that Antonio Artaud located at bottom of the theatre stage. The homage to Igory Mansotti is located in a kitchen with profiled wall-boards of unequal breadth as the oldest elements in the kitchen. Next to the drawers from the apothecary. The flooring and the Kvik kitchen are new. The homage is the newest element; though it comes out in the ensemble as the most established one.

It intercepts qualities of the space that without it would not have been manifest, but buried in the depths of potential and possibilities of what is already there. We ask: is the ornamental function restricted to the carvings in the darkened fir? Or, are the carvings what permits the rhythmic events—created between the bottom of the homage and the panel—to define a precinct beyond the functional perimeter of the human body? Does the ornamental function allow its users to occupy a space that exceeds their biological time-span, and defines them properly as dwellers?

Does the ornamental function extend to scan, intercept and frame the interplay of other elements—for instance how the thickness of the boards will refer to a bigger kitchen, or shop-keeping functions, consistent with the origin of the drawers from the commercial space of an apothecary? Would we readily pick up on other reverberations of consistency between non-same elements in the homage’s construction, without the ornamental pitch: which, when functionally defined, may be to remove the work one step off functionalities limited to and defined by the human body?

Here we are clearly pledged to discuss the co-existence in the world of a variety of bodies: the human body being only one of them. The qualities previously spotted by Mansotti as: “spectres and hauntings, beginnings and endings, things lost, and legacies that last and linger, words that do not stick, but work like shafts to weapons that do not show.” These are qualities that Mansotti associates with mountain-passes—such as Casera Kanin, where he comes from, in the Friuli mountains—which we could begin discussing in relation to homes, view in a new/different way.

Indeed, should we continue to consider homes as domestic isolates/enclosures? Or, could they be seen as something closer to Mansotti’s mountain-passes? Could we see them as a kind of crossroads, where social encounters become organised according to the task and the occasion? In all likelihood, the pandemic/lockdown reset our homes—repurposed as offices—as the traffic light of mediated alignments between materials found and marks made? Perhaps we do not need to become more intelligent, but rather become clever in a new way? Bjørn Blikstad asks in his works.

“More like furniture that comes with life-ways, winds and trade. Certainly not art.” Mansotti wrote of his work. To discuss these matters from a piece of paper evidently will not do. Maybe even the paper is counter-productive. Maybe we best could receive you June 1st 2023 at 17:00-19:00 hours without any statement. If you are of that heart, then burn after reading! We want the question to be raised: someone has asked it, and it is now out there. Because there might be a role in artistic research to relocate the options we have in the contemporary society.

With more limited resources than before, we cannot limit ourselves to being inventive pathfinders. We have to engage with goalseeking. What, under the circumstance, can we and do we want to do? Do we imagine that we going to do the same, only less of it? Or, what can we do to evolve humanly, environmentally and strategically as members of the contemporary society pledged to design?